“The smartest way to rig an election is to do so before the ballots have even been printed.”

In their book ‘How to Rig an Election’, Professor Nick Cheeseman and Dr. Brian Klaas describe the modern authoritarian’s toolbox in terms of six categories. Citing 21st-century examples from Russia and Kazakhstan, they identify as a common tactic the harassment of civil society (as well as opposition and the media) to generate a culture of fear and intimidation.

Since its illegitimate power grab in February 2021, the military junta in Myanmar has consistently targeted civil society and activists with human rights abuses in a calculated strategy to repress dissenting voices. As the junta ramps up preparations to hold illegal elections in 2023, the outlook for proponents of democracy and free speech is grim.

In an earlier post, we wrote about the three strategies the junta has used to crack down on opposition. Here, we take a closer look at a key pillar of the regime’s strategy to guarantee a result in 2023: the repression of civil society through violence, incarceration, and legislation.

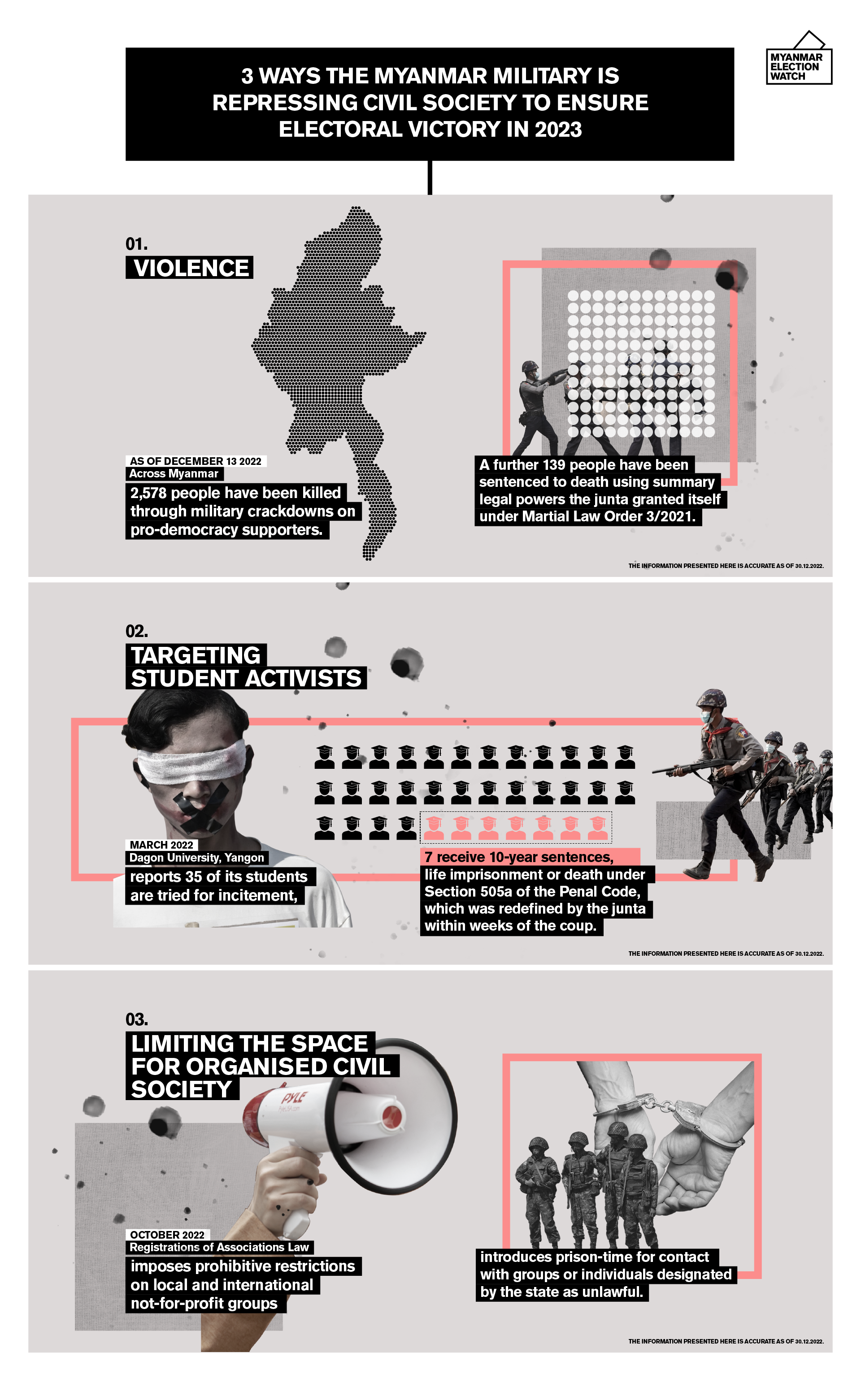

Violence has been the hallmark of the junta’s approach to civil society

The AAPP reports that to date, (December 13, 2022) 2,578 people have been killed through military crackdowns on pro-democracy supporters. From high-profile activist leaders to local figures within small communities, to complete bystanders including children, no one is safe.

Consider Than Myint, a 57-year-old farmer from rural Mandalay. Than Myint was detained in November 2021. Shortly after his arrest, Than Myint’s body was returned to his family with evidence of having been brutally beaten. His crime? Seemingly, leading a local charity that provided free funeral services in his village.

The world looked on in horror in July this year as Myanmar carried out four executions – the first known executions in the country for over thirty years. Among the four victims was the veteran activist Ko Jimmy. Ko Jimmy had spent most of his adult life in prison following his participation in the 8888 (1988) student uprising and the 2007 Saffron Revolution. Within a fortnight of the junta’s putsch, the junta issued arrest warrants for several prominent 8888 figures: in Ko Jimmy’s case, for allegedly inciting unrest and threatening “public tranquility” through social media posts critical of the coup. During his arrest in October 2021, Ko Jimmy was hospitalized and spent three days in intensive care. Soon after, the charges against him evolved from incitement into high treason and terrorism as state media released staged images of Ko Jimmy kneeling in front of a large cache of weapons, purportedly discovered during the raid that led to his arrest. Using summary legal powers which the junta had granted itself under Martial Law Order 3/2021, a military court sentenced Ko Jimmy and lawmaker Phyo Zayar Thaw to death under the Counterterrorism Law. Ko Jimmy’s body was not returned to his family. As of December 13, 2022, a total of 139 people have been sentenced to death.

Using post-coup legal revisions to target student activists

Students and former student activists have been targeted relentlessly by the junta. Dagon University Student Union reports that among 35 of its students who have been tried, seven have received sentences of ten years, life imprisonment, or death. Many of the others have received the maximum sentence for incitement, under Section 505a of the Penal Code, which was redefined by the junta within weeks of the coup. A 22-year-old executive member of Yangon University Students Union, Aung Hpone Maw, was sentenced to three years with hard labour, again under Section 505a, for his role in protests. In September, the current vice president of ABFSU, Wai Yan Phyo Moe was handed a further two years for political activities that took place prior to the coup, taking his total sentence to more than seven years.

Legislating to limit the space for organised civil society

In October 2022 the junta borrowed another page from Putin’s playbook. Russia’s ‘NGO Law’, introduced in 2012, required NGOs in receipt of foreign funding and participating in “political activities” to register with the government, submit detailed reporting, and in effect to refrain from criticism of the government. For individuals involved in NGOs, the law and any infraction brought with it the continual risk of severe prison sentences. The intention to chill the civil space was clear. (Sources: here, here, and here)

Myanmar’s latest legislation appears to seek a similar goal. The new Registration of Associations Law took effect on October 28 and imposes restrictions on not-for-profit groups, both local and international. The law mandates that at least 40 percent of board members be Myanmar nationals; stipulates that organizations must register for a government-issued certificate to operate; that they must submit quarterly reports to the local (junta-run) township General Administration Department; and forbids groups from “interfering in the internal affairs or politics of the state”. The law brings with it a penalty of up to five years for even indirect contact with groups or individuals designated by the state as unlawful or for “directly or indirectly harming the sovereignty, law and order, security, and ethnic unity of the state”. Not only will it therefore become administratively and financially more difficult to exist lawfully as a CSO, but the stakes have been raised for the individuals involved.

Activists’ resolve remains firm in the face of closing civil space

The junta’s attempts to chill dissent and opposition have been blatant. Yet despite the brutal tactics against activists described above, Myanmar’s civil society has so far stood firm. If anything, it appears such atrocities have redoubled activists’ resolve. While the impact of the Registrations of Associations Law remains to be seen, it is clear it will pose serious challenges for organized civil society and will severely limit the delivery of international aid. It is clearer still that in such a closed, repressed space for civil society, no election can be considered legitimate.

Right-click and download this infographic for use in your communications, content or articles.